The Radicals Who Made a Revolution

A few years back, somewhere near the beginning of the lingering housing crisis, I ran across an article talking about parallels between our own present financial woes and those of the American colonists struggling with the collapse of their economy after the high-flying days of the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763. Benjamin Franklin, just returned after considerable time as envoy to London, lamented that rents and land values had “trebled in the past six years,” due to the British practice of quartering troops and supplies in private buildings and on lands for which no rent or price seemed too high. When the troops were sent home, however, the artificial juggernaut of prosperity fell apart. Rented properties were suddenly vacant; overvalued lands and homes were seized. Trouble that sounds familiar to all of us today soon began. Reading of all this provided the first tug of personal connection with events that I knew about vaguely but had never felt, a moment of the sort in which all my histories have been born.

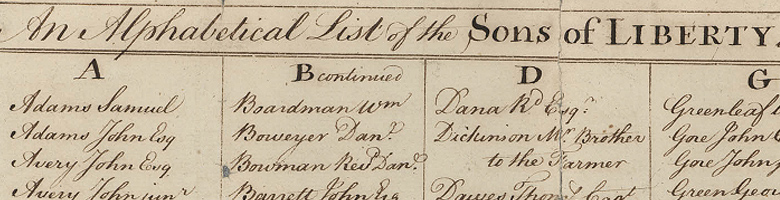

As I continued to pull on that thread of history’s sleeve, and as I came to realize that there had never been a book about the secret, radical group of men in the colonies who were responsible for leading us from those first stirrings of discontent into a revolution a decade later, I became hooked. We might have heard bits and pieces of the story, but the entire saga, I saw, had never been told from beginning through middle to end. This has always been my interest in writing history: to tell a fascinating, little-known story “behind the story.”