Function

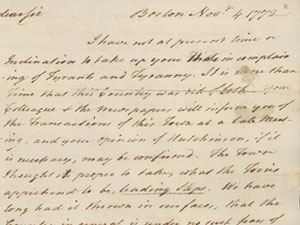

Soon after the formation of the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the network of Committees of Correspondence which soon sprung up all over Massachusetts, in the spring of 1773 Committees of Correspondence were established in the colonies of Rhode Island, Conneticut, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. By February 1774, eleven of the Thirteen Colonies, excluding Pennsylvania and North Carolina, had established networks of Committees of Correspondence. In terms of power, by early 1774 the Committees of Correspondence had superseded the colonial legislature and royal officials in the Thirteen Colonies. The Committees of Correspondence were influential in revolutionizing the town meeting from discussions of local matters to far-reaching global politics. In effect, the town meeting became the action-level for the Patriot cause. These meetings served as a means for the concerned citizenry to voice their opinions about the grievances they had with Britain. The primary function of the Committees of Correspondence was the championing and implementation of the Patriot cause through diplomatic means. The vast network of Committees of Correspondence served as a powerful pipeline through which information could be transmitted to all of the Thirteen Colonies. The Committees of Correspondence served as a well-calculated Patriot network for the dissemination of news and information as it related to grievances with Britain from the major cities to the rural communities. The Committees of Correspondence were responsible for ensuring the information they disseminated was accurate and reflected the views of their local parent governments on particular issues, the colonial interpretation of British policy, and that the information they issued was sent to the proper factions. Information was disseminated by the Committees of Correspondence throughout the Thirteen Colonies through pamphlets and letters carried by post riders or onboard ships. Additionally, newspapers served as vital tools and communiqués for the network of Committees of Correspondence. The Boston Committee of Correspondence relied on the Boston Gazette and Massachusetts Spy as a principle means of disseminating information regarding the Patriot cause and grievances with Britain. The Committees of Correspondence promoted manufacturing in the Thirteen Colonies and advised colonists not to buy goods imported from Britain. The goal of the Committees of Correspondence throughout the Thirteen Colonies was to inform voters of the common threat they faced from their mother country – Britain. The majority of the members of the Committees of Correspondence were also members of their local chapters of the secret Patriot organization the Sons of Liberty. They set up espionage networks to identify disloyal elements and disenfranchised royal officials. The Maryland Committee of Correspondence was influential in establishing the First Continental Congress. They convened in Philadelphia in September and October of 1774 to petition Britain to repeal the Intolerable Acts. Committees of Correspondence worked in conjunction with the Committees of Safety, formally Councils of War – which had been in existence since the 17th century. The Committees of Safety, like the Committees of Correspondence, were formed on the eve of the American Revolution throughout the Thirteen Colonies in response to tensions with Britain and empowered committees to “alarm, muster, and cause to be assembled” as much of the provincial militia as needed at any time. The Committees of Correspondence and the Committees of Safety, most notably in Massachusetts, were influential in the organizing, training, and arming of Patriot militias and establishing companies of minute men prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775, at Lexington and Concord. Committees of Correspondence provided the political organization necessary to unite the Thirteen Colonies in opposition to Britain. As a political entity, the Committees of Correspondence were replaced during the American Revolution by the more formal and qualified Provincial Congresses but they still continued to function at the local level.