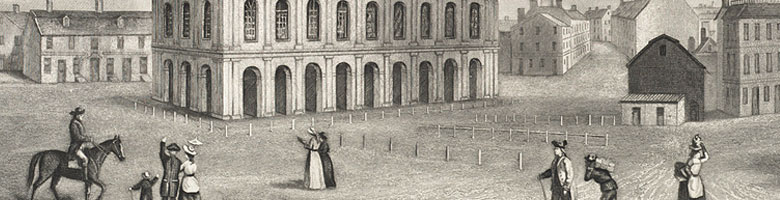

On Monday, November 2, 1772, at a town meeting held at Faneuil Hall, by the urging of Samuel Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren, James Otis, and other Patriot leaders, the Boston Committee of Correspondence was formed. The meeting held at Faneuil Hall garnered enough support to vote in a resolution to create the Boston Committee of Correspondence. The Boston Committee of Correspondence was the first standing Committee of Correspondence formed in the Thirteen Colonies.

On November 5, 1773, Guy Fawkes Day (celebrated as Pope’s Day in colonial Boston), Samuel Adams called a town meeting at Faneuil Hall in response to the “tea crisis” and declared anyone who aids or abets the “unloading receiving or vending the tea is an enemy to America!” It was at this meeting Samuel Adams was appointed to handle the “tea crisis”. The first large-scale organized meeting to discuss the “tea crisis” occurred at Faneuil Hall on Monday, November 29, 1773 – the day after the Dartmouth arrived. The Dartmouth was the first of the Tea Party Ships to arrive at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. Prior to this, smaller scale meetings had been held at Faneuil Hall to discuss the “tea crisis”. By this time, Boston had become a hotbed of dissent and radicalism, and thousands gathered from Boston and surrounding towns to meet at Faneuil Hall. The meeting was organized by the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Sons of Liberty, both of which were under the leadership of Samuel Adams. On November 29 at Faneuil Hall, they resolved that “as the town of Boston, in a full legal meeting, has resolved to do the utmost in its power to prevent the landing of the tea.” The gathering attracted so many of the concerned citizenry that the meeting had to be quickly relocated to the Old South Meeting House because Faneuil Hall could not accommodate the masses of people. Old South Meeting House was the largest public building in Boston at the time and thus became a suitable alternative location to relocate the meeting. Samuel Adams, in a letter to a colleague, wrote about the numbers of people present at the meeting, “The people met in Faneuil Hall, without observing the rules prescribed by law for calling them together…they were soon obliged for the want of room to adjourn to the Old South Meeting House; where were assembled upon this important occasion 5000, some say 6000 men, consisting of the respectable inhabitants of this and the adjacent towns. The business of the meeting was conducted with decency, unanimity, and spirit.” The meeting first held at Faneuil Hall and relocated to the Old South Meeting House on November 29 was the first of a series of meetings which culminated in the December 16, 1773 Boston Tea Party.