From the moment they set foot in Boston, the redcoats were constantly at odds with the town’s inhabitants. By the beginning of March, 1770, tensions seemed to reach a boiling point. On the evening of March 5, Private Hugh White was under assault by a crowd of boys throwing snowballs, oysters in their shells, stones and clubs. Moments later, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene along with grenadiers from the 29th Regiment. The soldiers formed a half circle around White, with Captain Preston standing in front of his men to keep the peace. According to witnesses, a club flew through the air striking one soldier in the head, which caused him to lose his balance, and discharge his musket. Thinking they had been given the order to fire, the other soldiers also discharged their weapons into the crowd, leaving five civilians on the ground, mortally wounded.

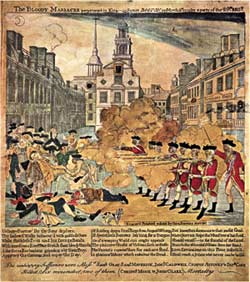

The very next day, John Adams received a loud knock on his door. He was asked to defend the soldiers and Captain Preston, as nobody else would take the case. Without hesitation Adams agreed to defend the soldiers and their captain. Above all, John Adams believed in upholding the law, and defending the innocent. Adams was convinced that the soldiers were wrongly accused, and had fired into the crowd in self-defense. But in the months that followed, his second cousin, Samuel Adams did everything in his power to paint the redcoats as the troublemakers who started it all. Public vigils were held to remind the people of the brutal oppressors who killed their friends. Paul Revere altered an engraving by Henry Pelham commemorating the bloody massacre on King Street to show the redcoats taking great pleasure in firing at the town’s people, and also depicting Captain Preston standing behind his men while giving them the order to fire.