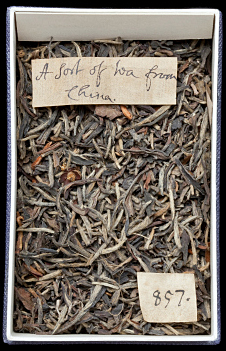

A lengthy, illustrated article appeared in the December 1852 edition of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine recalling the events leading up to the 1773 Boston Tea Party and the defiant role New England women played in setting the course for opposing George III’s tax schemes. A portion of the article reads as follows:

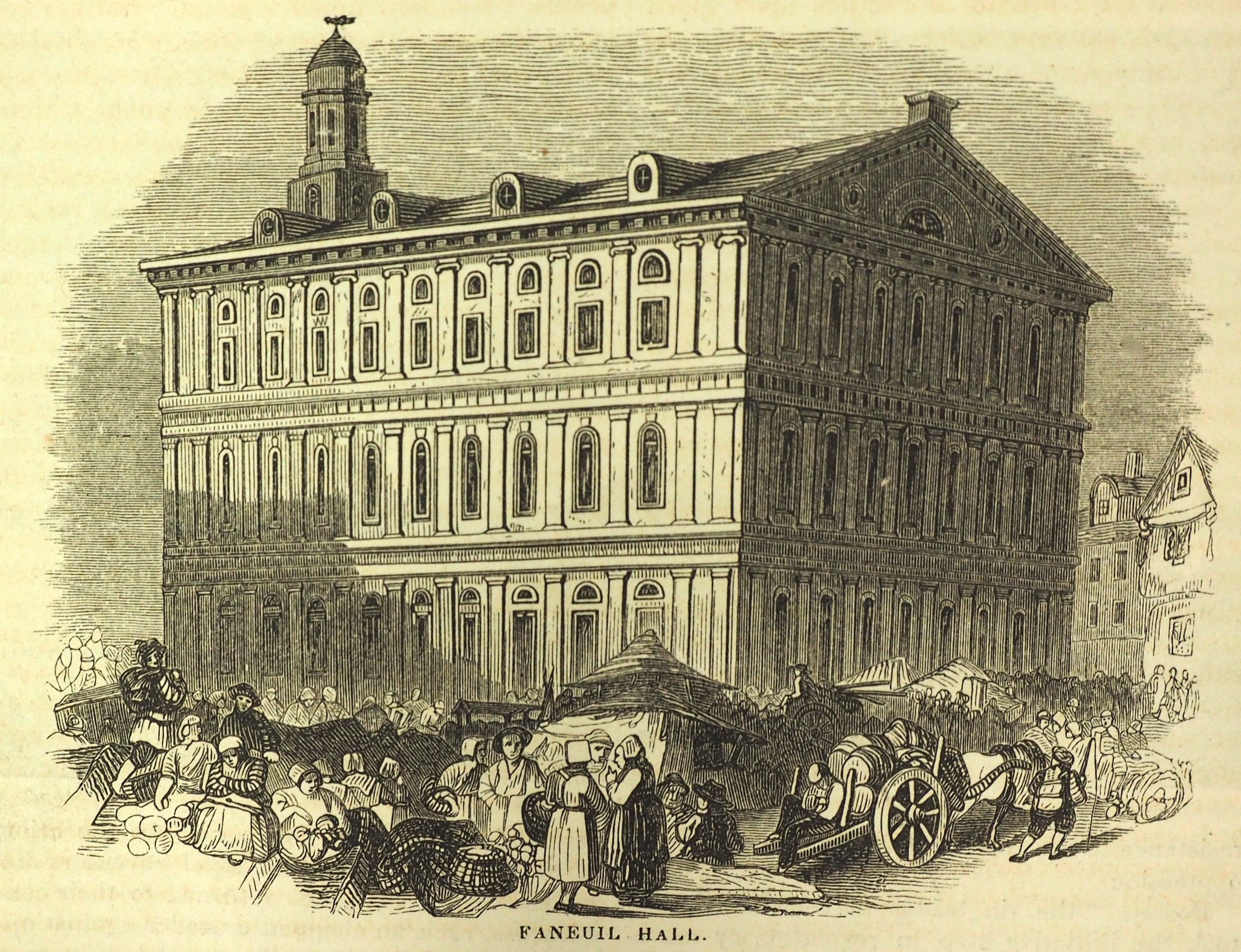

In America meetings were frequently held and men thus encouraged each other by mutual conference. Nor did men, alone, preach and practice self-denial of the dreaded tea; American women cast their influence into the scale of patriotism as they assembled in Faneuil Hall, there to declare that they would “totally abstain from the use of tea,” and other proscribed articles.